The Cherokee Removal Part One

The earliest Cherokee to remove to the Indian Territory did so voluntarily when a group of more than 2,000 moved there from Georgia. By 1838 these Cherokee were settled in the Territory but large bands of the Cherokee remained in Georgia, resistant to the provisions of the Indian Removal Act, claiming that the tribal leaders who had signed it lacked the authority to do so, and petitioning through the federal courts for exemptions. They made some progress in the legal system, but in 1831 the United States Supreme Court found that the Cherokee were not a sovereign nation and therefore lacked status before the Court.

Complicating matters for the Cherokee was the 1829 discovery of gold on the lands they occupied in Georgia, and pressure from gold speculators led to the above Supreme Court decision. In an 1832 decision, the Supreme Court ruled that the state of Georgia could not treat with the Cherokee, nor extend state laws to land occupied by the Cherokee, as those powers were reserved to the federal government by the Constitution. This decision was one cause of Andrew Jackson’s dissatisfaction with the Supreme Court and it led Jackson to challenge the court to enforce it, albeit derisively. The court affirmed his powers which he was hesitant to use.

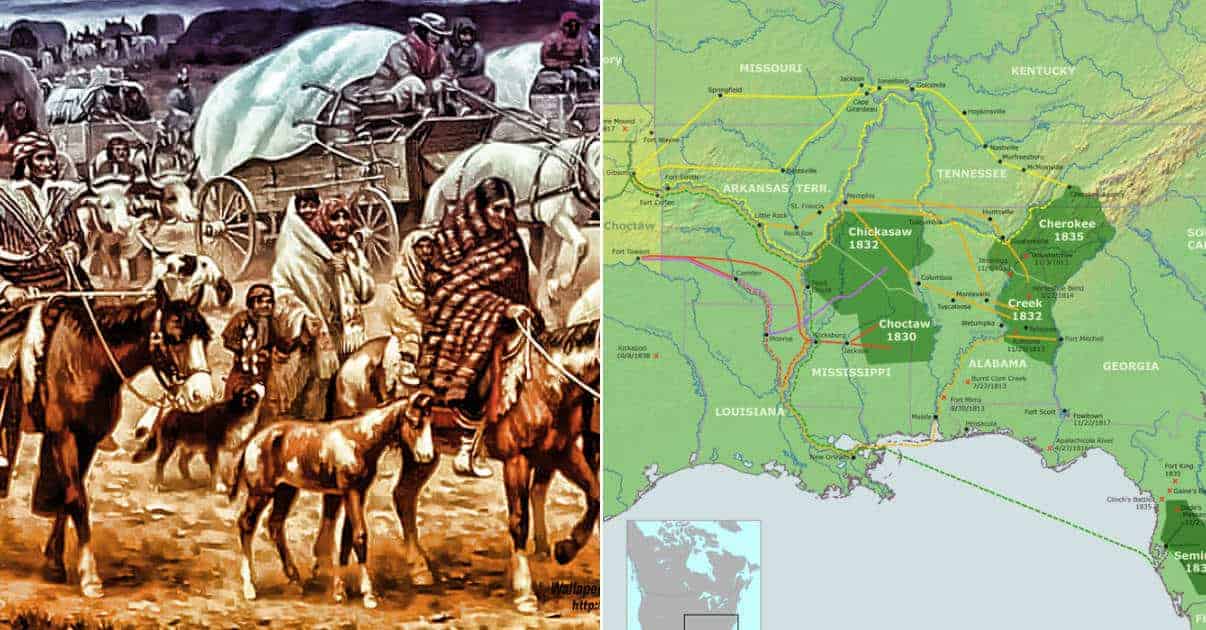

It was Martin Van Buren, as Jackson’s successor, who authorized the states of Alabama, Georgia, Tennessee, and North Carolina to use their militia, supplemented by federal troops, to collect the Cherokee in the area of Cleveland and Chattanooga, Tennessee. As the Cherokee were removed the land which they had occupied was surveyed, divided, and made available for settlement. As with the other relocated tribes, Cherokee who agreed to abide by the laws of the state and occupy individual plots of land under state and federal law were allowed to remain. Many agreed to these terms. Others removed to the vicinity of the Great Smoky Mountains.

Those who did not were rounded up by the various state militia and once they were gathered in Tennessee, the federal government assumed responsibility for their care and removal to the Indian Territory. Suffering of the Cherokee began in the camps in Tennessee long before the western migration began. Disease was rampant as was insufficient rations for the Indians, who also suffered from the rampant racism of the day. Those attempting to purchase supplies were often swindled by unscrupulous agents, delivered food was frequently short-weighted.

Although it was summer when the round-up of the Cherokee was completed, movement to the west was delayed by a variety of factors, including the heat. Although the majority of the Cherokee held in these internment camps still resisted the idea of moving to the Indian Territory by autumn it was evident even to their most reluctant leaders that failure to do so meant the end of the Cherokee Nation, through attrition. American General Winfield Scott awarded contracts to Cherokee companies to remove the remaining 11,000 or so Cherokee, and their primary chief, John Ross, agreed to the removal and to lead the migration.