The Cherokee Removal Part Two

If the actual decision to relocate the Cherokee to lands which were unfamiliar to them was cruel, the manner in which it was carried out was far worst. Bureaucratic incompetence, malfeasance, outright swindling and theft, and mismanagement combined with the horrendous weather and the sheer distance to be traveled to wreak havoc upon the Cherokee. Chief John Ross organized wagon trains for the removal, purchased supplies, obtained a steamboat, and arranged for each of the trains to carry medicines, trained doctors, and sufficient guides. Different routes were selected for the trains to ease pressure in supply stations. Ross purchased additional shoes and clothing for each train.

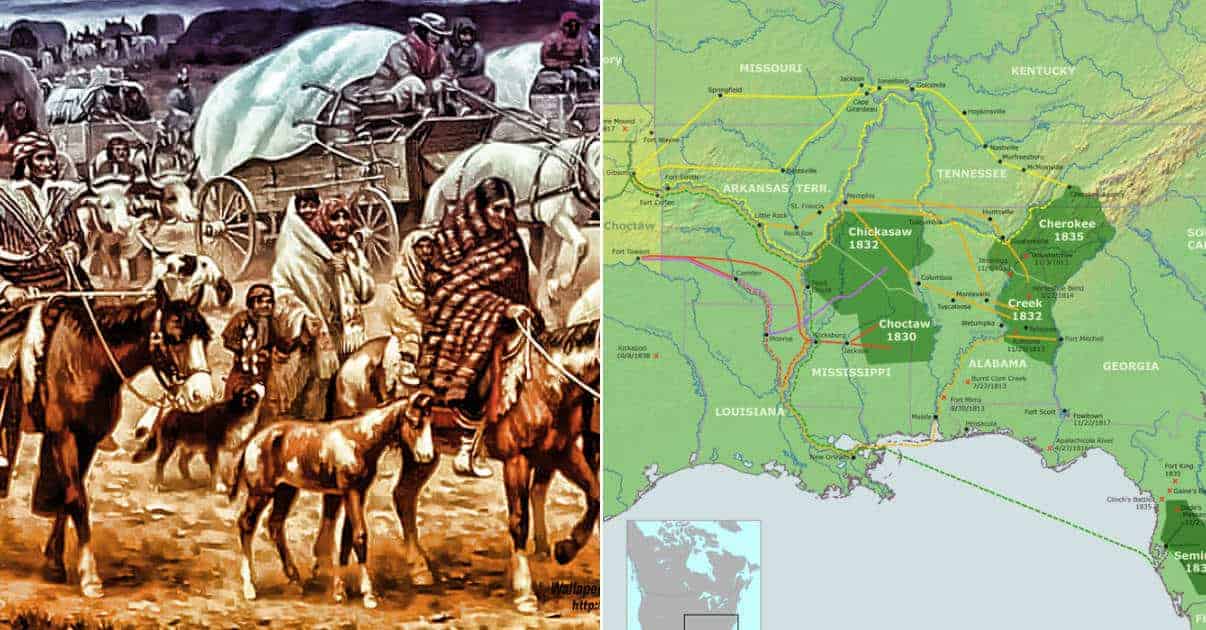

Depending upon the route taken, the westward bound Cherokee traveled through Tennessee, Kentucky, Illinois, Arkansas, Mississippi and Missouri. The trip could be as long as 2,000 miles and because of conditions found along the way, often much longer. Many towns in the Cherokee’s path refused to allow them entry after hearing of the disease present in some of the trains, forcing them to follow a circuitous route to avoid confrontation, a situation the Choctaw had also faced. The weather was freezing, damp, and often icy conditions forced a halt. Sitting idly in crowded camps, supplies dwindled and disease increased.

The twelve separate wagon trains left the internment camps between early October, 1838, and March, 1839. In addition there was an attachment conducted by John Ross himself, which departed Agency Camp in Tennessee with 219 Cherokee in November 1838 and arrived in Tahlequah, Indian Territory in late March 1839, escorting 231 Cherokee, having picked up some stragglers in the trek west. Most of the trains heading westward were not so fortunate. Many of the wagon trains found their numbers depleted through desertion, as Cherokee departed the removal as they passed through the still largely unsettled wilderness between the cities.

The number of deaths which occurred during the westward migration has been disputed since the removal was actually in progress. Upon completion of the westward movement Chief John Ross submitted his expense reports to the United States Army. The Army, after studying the reports, considered many of them to be falsely inflated. In his accounts Ross claimed that he received higher numbers of rations than army disbursal records at the various supply sites recorded. His claims were consistently in conflict with army records throughout the trek. This indicated he had to feed many more than arrived, and their absence was explained as death or desertion.

Before the Trail of Tears migration by the Cherokee their tribal census indicated a population of about 16,000. Twelve thousand made the trek to the Indian Territory successfully, leading some contemporary scholars to report that 4,000 or more died during the removal. This figure fails to account for the 1,500 or so that remained in the east, primarily in the region of the Great Smoky Mountains, and others whom remained in the Piedmont of South Carolina. The number of deaths from disease and malnutrition are more likely in the area of 2,000, still a regrettable figure, but not one to qualify, as some extremists would have it, as a genocide.