Aftermath

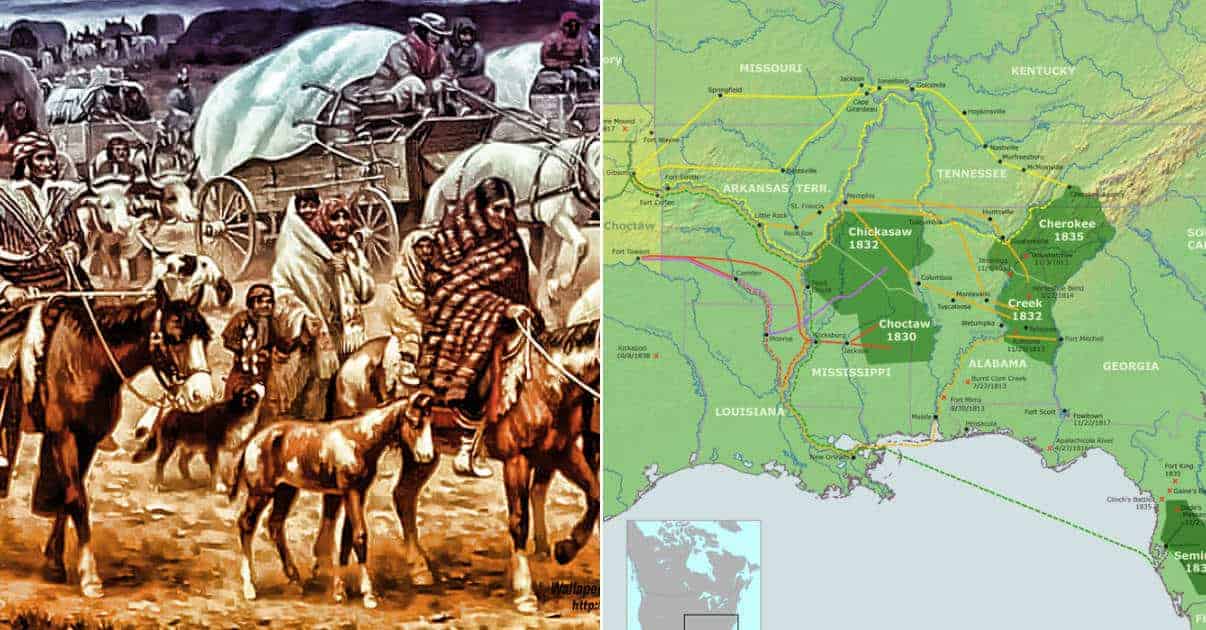

In American history the Trail of Tears and the forceful removal of the eastern tribes is considered an act of genocide by some, an unfortunate incident by others, and it is one of the least understood actions in American history. Although the term is usually referred to only in the context of the Cherokee removal, it encompasses a great deal more than the relocation of that tribe. In many instances Indian leadership was complicit with and profited from the removal. In others it was forcibly opposed by the Indians, leading to even greater suffering by their people.

Andrew Jackson is blamed by both sides which condemn the actions under the Indian Removal Act, but he is just one of several Presidents who directed the removal of the Indians under the Act’s provisions. Martin Van Buren and John Quincy Adams were both involved as well. Later other Presidents would order other relocations. Adams refused to use American Army troops to enforce federal law in Georgia and Alabama, allowing both states to initiate their own seizure of lands occupied by the Indians. Both Adams and Van Buren ( and to an extent Jackson) felt that the use of federal troops would lead to conflict with state militia and possible civil war, and none wanted to assume that risk.

The American public and political groups argued strongly against the Indian Removal Act, especially those of the Northeastern states and the newer states of the west, such as Ohio and Indiana. New England opposition was especially strong. Daniel Webster and Henry Clay, political adversaries in other areas, opposed the removal. In Tennessee Congressman David Crockett risked his political career by arguing forcibly against the act, angering the President, a fellow Tennesseean. Crockett had been seriously considered a possible Presidential candidate until the Jackson Machine in Tennessee ensured he wouldn’t be re-elected to Congress following his opposition. Defeated, Crockett went to Texas. Before the Cherokee removal began, he was dead at the Alamo.

Another forgotten victim of the forced removal are the people of the Chickasaw Nation. In 1832 the Chickasaw agreed to move to the Indian Territory as soon as they had the available resources to effect the relocation. In return the federal government agreed to provide financial compensation, protect the Chickasaw from all enemies, and provide suitable land in the west. Before the terms of the agreement could be complied with, pressure on the Chickasaw land from white settlements forced the tribe to pay tribute to the Choctaw to be allowed to live on Choctaw land in the Indian Territory. The Chickasaw were assimilated into the Choctaw.

By the end of the Jackson Administration in 1837, approximately 46,000 members of the eastern tribes had been forcibly or voluntarily removed to the Indian Territory west of the Mississippi. This was just under half of all the American Indians who were eventually removed under the terms of the Indian Removal Act and the ensuing treaties with the tribes involved. The Cherokee removal had yet to begin when Jackson left office. Under Jackson, 25 million acres of land, primarily located in the slave states of the south, were opened to planters and other settlers.