ADVERTISEMENT - CONTINUE READING BELOW

Justinian II

Justinian II was one of the most power-hungry and ruthless rulers of the Middle Ages. He was the last Byzantine Emperor of the Heraclian Dynasty and, following on from the rule of his father, Constantine IV, was determined to restore the Roman Empire to its former glory. However, while his father had also been a strongman, he also had charisma and political finesse, allowing him to keep opposition at bay, Justinian II had little of this and made many enemies. However, even when he was deposed, he was able to gather himself and launch one of the most notable comebacks of all time.

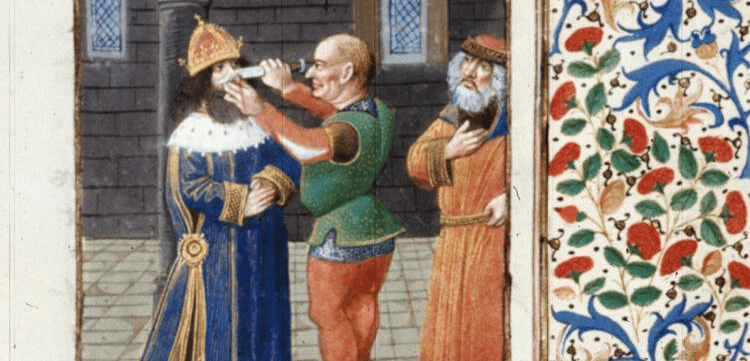

Born in 668 or 669, Justinian II was declared Emperor in September 685. He managed to cling on to power for a decade. However, over the years, opposition to his rule kept on growing, with his enemies forming alliances against the unpopular Emperor. As well as frustrating tribal leaders, he also angered the wider population through his taxation policies. Eventually, in 695, the people rose up under Leontios. The Greek declared himself Emperor and Justinian was sent into exile. As was common in Byzantine culture, his nose was cut off, not just to humiliate him but to ensure he would be less likely to become popular again and try and regain power.

In his absence, Leontios was usurped by Tiberius, but few people in Constantinople missed Justinian. He was able to contact some old friends and allies while living in exile in modern-day Crimea. In the year 705, he had enough men under his command to try and make his comeback. Justinian sailed through the Black Sea back to Constantinople. He survived a terrible storm and saw this as a sign of his destiny. When he and his 15,000-strong army finally reached the city, however, the people refused to open the gates to them. Undeterred, Justinian found a way in through an old aqueduct. He had returned, and, though the rules declared that a deformed man could never rule, he ignored this.

Justinian’s second term as Emperor was even more brutal than his first. He slaughtered his opponents, including the two men who had ruled while he was in exile. However, before long, he was facing trouble again. A second uprising was launched. Justinian was captured and executed by the side of a road in December 711. He may have engineered a comeback of epic proportions, but he was still reliant on the goodwill of the people, and his power-hungry nature was to be his downfall.