When the eruption of Vesuvius in 79 AD destroyed Pompeii and Herculaneum, the towns became inadvertent time capsules for the Roman world. Artifacts and buildings allowed archaeologists an insight into everyday Roman life that books alone could not convey. However, it is the victims of the eruption who genuinely fascinate people- especially those whose final moments are preserved as body casts. However, an eternity preserved in plaster or a museum is no kind of immortality. These people have lost their individuality because we do not know their names.

Names do survive in the two towns. A shop notice from Pompeii tells us it was owned by an outfitter named Marcus Vecilius Verecundus. Elsewhere, graffiti declares the gladiator Celadus was “the girls’ idol” while we know that the politically forthright barmaids of Asellina’s tavern: Aegle, Smyrna, and Maria were Greek, Syrian and Jewish from the ethnic origin of their names. These isolated fragments are just fleeting ghosts of long-lost people. We know nothing more about them. However, in some cases, it is possible to gather up various pieces of an individual’s life and piece them together like a jigsaw to form a picture of who they were.

ADVERTISEMENT - CONTINUE READING BELOW

Marcus Attilius

Grafitti preserves the names of a number of gladiators from Pompeii and Herculaneum. Aside from the gladiator Celadus, who we know from graffiti from the House of the Gladiators in Pompeii, various other names appear in cartoons depicting the outcomes of fights which fans of the games scratched into the tombs that lined the roads leading into and out of Pompeii, particularly around the Nucerian gate. There is Princeps (the chief) and Hilarius (Merry). These single names are the stage names of otherwise anonymous slaves forced to fight in the arena. However, the name of one fighter stands out.

Marcus Attilius was a gladiator, but his name shows us he was no slave. ‘Marcus’ was the praenomen of a free man and Attilius his gens or clan name. Attilius’s freeborn status means he had entered the arena of his own free will; he had, in the words of Livy, “put his life’s blood up for sale.” However, while the occasional Roman aristocrat might take part in a novelty bout (The emperor Commodus, in particular, liked to fight under the name Hercules the Hunter), volunteering to compete for a ludus was quite a different matter.

For although gladiators were the rock stars of the Roman people, heartthrobs, and heroes of the masses, they were also tainted with the stain of death. To fight as a volunteer, a free man was taking on that stain. When he signed a contract with the ludus, he not only gave up the next few years of his life but also his honor-permanently. He was also giving up his freedom because for the period of the contract, the ludus essentially owned him. For a man to do give up all this, they had to be desperate not for fame but for money.

ADVERTISEMENT - CONTINUE READING BELOW

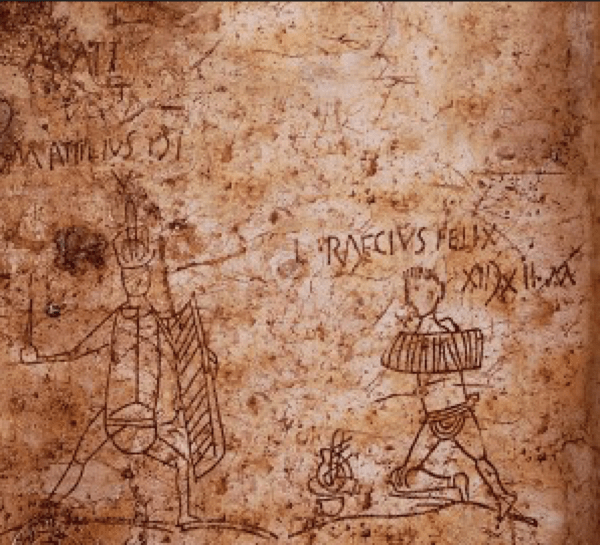

The match cartoons tell us a great deal about Marcus Attilius, the gladiator. We know that he won his very first fight in the arena, during games in Nola. A ‘T’ for Tiro– a novice gladiator, after Attilius’s name indicates this. Attilius was fighting a seasoned veteran of the arena, Hilarious, who, the numerals after his name show had fought 14 matches and won 12. However, on this occasion, the V for vicit came after Attilus’s name. Hilarius instead had to settle for an M for Missus, which means that even though he lost the match, he did not lose his life.

Attilius’s next fight was against another veteran Felix who had won all his previous 12 contests. However, Felix’s luck ran out when he encountered Attilius in the arena. He too is marked as a reprieved loser. So how could Attilius go from being an unseasoned novice to beating two veteran gladiators? Given his evident skill with the sword, Attilius was most likely an ex-soldier fallen upon hard times. Volunteers were often ex-army men who could not make a living in civilian life. They had no trade but blood, and the discipline and comradeship of gladiator schools were very similar to that of the military life.

We know Attilius fought as a murmillo from the armor he wore in cartoons. However, we do not know what he looked like- unlike our next Pompeian citizen.