ADVERTISEMENT - CONTINUE READING BELOW

9. Mary Magdalene, as understood in popular religious memory, is the conflation of multiple biblical women, in addition to being theorized that her canonical depiction itself is an amalgamation of many

Mary Magdalene was a Jewish woman who is depicted within the four canonical gospels of Christianity as a traveling companion and follower of Jesus. Mentioned twelve times across the gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John – and consequently more often, in fact, than many of the male apostles – Mary Magdalene was a witness to the crucifixion, burial, and resurrection of Jesus; as a result, Mary Magdalene is generally considered one of the most important figures in early Christianity and was canonized in the pre-Congregation era. Most likely born in the town of Magdala, a fishing village on the western shore of the Sea of Galilee, Mary, “from whom seven demons had gone out”, was one of several women who traveled with Jesus and supported his ministry “out of their resources”, suggesting she was independently wealthy; these women were critical to the continuation of Jesus’s movement, and it is noteworthy that whenever they are mentioned that Mary is always first among them.

In the centuries since the events described in the gospels, Mary Magdalene has been the subject of numerous conspiracy theories concerning an alleged relationship with Jesus. These unproven speculations, revitalized in the 21st century by the bestselling Dan Brown novel The Da Vinci Code, contend that Mary and Jesus were wed and potentially even had children; there is no historical evidence to support either Brown’s interpretation or any wider theory on this subject, yet it has endured in popular memory nonetheless.

ADVERTISEMENT - CONTINUE READING BELOW

In no small part, this public proclivity is due to the historical conflation of Mary Magdalene with other, less classically virtuous women, who appear in Christian scripture. During the Middle Ages, Mary Magdalene was repeatedly misidentified with a number of other women and combined into a single figure; these misunderstandings, often considered to have begun with a homily given by Pope Gregory I, continue to the modern day, with popular and religious understanding awash with biblical inaccuracies concerning Mary Magdalene.

First, Mary Magdalene was conflated with Mary of Bethany: a devout follower who was responsible for anointing of the feet of Jesus according to the gospels. Secondly, and more infamously, Mary Magdalene was confused with an unnamed “sinful woman” who also anoints Jesus’s feet; this conflation has produced centuries of popular belief that Mary Magdalene was a prostitute, resulting in her becoming the patron saint of “wayward women” and several female borstal institutes and asylums are so-named for her. Interestingly, it has even been proposed, including by Saint Ambrose in the 4th century CE, that Mary Magdalene was herself multiple people, with different Marys present at the crucifixion and the resurrection.

ADVERTISEMENT - CONTINUE READING BELOW

8. The epic poet Homer, author of The Iliad and The Odyssey, was most likely, at least in reference to his capacity as the author, multiple writers across several centuries

Homer is an ancient and legendary Greek writer, often attributed as the author of The Iliad and The Odyssey: iconic epic poems depicting the siege of the city of Troy, the quarrel between King Agamemnon and Achilles, and the homeward journey of Odysseus, King of Ithaca, after the Greek victory and the fall of Troy. No documentary existence of Homer survives except for his great works, with all accounts of his life based on subsequent ancient Greek traditions; Herodotus, for example, asserted that Homer was alive less than 400 years prior to his own time, placing him no earlier than 850 BCE, whilst modern historical opinion typically agrees that the poet was alive around 700 BCE.

Laid out in Homeric Greek, also known as Epic Greek, the language displays a mixture of different dialects, notably Ionic and Aeolic, dating to different centuries; as a result, it has been speculated that the poems were originally transmitted orally and were only later translated into the written form. The current historical consensus is divided in two: one which contends Homer did indeed exist and was the sole author of these works, and another which asserts that the Homeric poems were the work of many contributors in which “Homer” merely serves as a label for the poetic tradition they followed.

A common feature of the Greek oral culture was oral-formulaic compositions: a poem composed on the spot through the use of repetitive story elements and stock phrases. In light of this, it has been proposed that Homer’s works, in particular The Iliad, was the product of a “million little pieces” style of poetic design, wherein the epic poem underwent gradual standardization and refinement over a period of several centuries. Most scholars agree that Homer’s works were incrementally altered during the ancient Greek period, notably the addition of the Doloneia in Book X of The Iliad; therefore, whilst likely borrowing elements from previous bards, according to this theory Homer would have been the original author whose work was then subsequently “completed” by successor generations. Another branch, highlighting the absence of corroborating historical evidence for the life of Homer, contends that Homer as an individual person might not have even existed, with his name instead referring to a series of oral-formulas rather than a specific original author.

ADVERTISEMENT - CONTINUE READING BELOW

7. Ragnar Lodbrok, the legendary Viking warrior-king, was most likely a compilation of several similarly named Norse rulers who pillaged during the 8th and 9th centuries

Ragnar Lodbrok, also known as Ragnar Lothbrok or “Ragnar Shaggy Breeches”, was a legendary Viking ruler dating from the 9 century CE who appears as one of the most prominent, yet mysterious, heroes throughout the Old Norse sagas.

In “The Tale of Ragnar Lodbrok, a 13th-century Icelandic saga, Ragnar is situated as the son of the Swedish King Sigurd Hring; after defeating his elder brother Harald Wartooth, Sigurd ruled from approximately 770 CE until 804 when he was succeeded by Ragnar. Next identified as leading the Siege of Paris in 845 CE, the culmination of a massive Viking invasion into Frankish territory, under the name of “Reginherus”; amassing a fleet of 120 ships and more than 5,000 warriors, Ragnar’s forces repeatedly defeated those of Charles the Bald and successfully sacked Paris. Finally, Ragnar’s last appearance is in that of “The Tale of Ragnar’s Sons”, an account of his son’s vengeance of his murder at the hands of King Aella of Northumbria; supposedly put to death by Aella at some point around 865 CE, the sons of Ragnar, led by Ivar the Boneless, organized The Great Heathen Army and invaded Anglo-Saxon England.

In contrast to the sons of Ragnar, in particular Ivar the Boneless, whose histories were meticulously recorded by sources such as the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, the modern historical opinion is that “there is no evidence that Ragnar himself ever lived, and he seems to be an amalgam of several different historical figures and pure literary invention”; in spite of this, however, it is unquestionable that a man of great significance was the father of the so-called sons of Ragnar and thus “scholars in recent years have come to accept at least part of Ragnar’s story as based on historical fact”.

As a result, several individuals spanning many generations have been suggested as the composite parts which were later assimilated into the legendary myth of Ragnar Lodbrok in an effort by 12th-14th century Norse chroniclers to reconcile various outstanding chronologies. Among these unique persons believed to have been, either intentionally or unintentionally, merged into the Ragnar Lodbrok of legend is the “Reginherus” who was responsible for the aforementioned Siege of Paris, King Horik I (d. 854 CE), King Reginfrid (d. 814 CE) of Denmark, and a figure from the Irish Annals named Ragnall.

ADVERTISEMENT - CONTINUE READING BELOW

6. Lycurgus of Sparta, responsible for the creation of the ancient Spartan constitution, was probably not a single person but a composite fiction offering an individual face to several generations of reforming lawmakers

Lycurgus (b. 820 BCE) was a lawgiver of the ancient Greek city-state of Sparta, traditionally credited with the communalistic and militaristic reforms of Spartan society; among these reforms, all of which promoted the characteristic Spartan triple virtues of equality among citizens, military fitness, and austerity, was the Great Rhetra: the oral constitution of Sparta.

The son of the King of Sparta, Lycurgus supposedly embarked on a prolonged traveling exile wherein he studied the laws of the other Greek cultures and beyond before returning to his home city at the behest of his people to become their ruler. Recognizing the need for change in Sparta, Lycurgus allegedly consulted with the famed Oracle at Delphi and produced his grand reforms. After a period of great leadership Lycurgus departed to the Oracle once more to make a sacrifice to Apollo, but not before binding his people under oath to adhere to his laws until his return; praised for his laws as indeed excellent by the Oracle, Lycurgus supposedly then starved himself to death to compel the people of Sparta to forever be bound by their oath and to uphold his reforms.

In spite of this surviving biography, the preponderance of information concerning Lycurgus originates from Plutarch’s Life of Lycurgus: an anecdotal collection of stories written around 100 CE regarding the ancient lawgiver. By Plutarch’s own stark admission, nothing involving Lycurgus contained within his work can be known for sure and consequently it has been widely speculated that Lycurgus himself might be little more than a composite fiction for the foundational principles of the nation-state of Sparta. Representing either an entirely symbolic individual, modeled on the god Apollo who was later merged with Lycurgus within Spartan religious culture as a person of special veneration, or a combination of several reformist rulers of the city-state between the 10th and 6th centuries BCE, historical consensus agrees that the Lycurgus was not a singular individual.

ADVERTISEMENT - CONTINUE READING BELOW

5. Betty Crocker was not a real person, but instead a fictional character created by an advertising company and played by multiple actresses

Betty Crocker was a fictional character created for use in advertising campaigns for food and recipes by the Washburn-Crosby Company in 1921. Used to promote branded goods, with the Betty Seal of Approval becoming a hallmark of American households during the 1920s-1960s, Betty Crocker was designed in such a way as to allow the otherwise faceless corporation to provide personalized responses to consumer questions in a friendly manner; the name Betty was selected as it was considered a stereotypical all-American name, whilst Crocker was chosen in honor of a director of the Washburn Crosby Company.

Despite the popularity of the individual publicly known as “Betty Crocker”, with Fortune magazine in 1945 naming Betty as the second most popular woman in America behind First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, even as a fictional creation she was never merely one person. Originally performed on radio by Blanche Ingersoll from 1924, making her debut in “The Betty Crocker Cooking School of the Air”, the radio show remained on the air until 1953. This anonymous figure was finally unveiled in a 1936 portrait painting commissioned by the company depicting the legendary celebrity; designed with a “motherly image” that “blended the features of several Home Service Department members”, it was painted by Neysa McMein and was subtly changed over the years to accommodate the changing cultural perception of the American homeowner, including a final depiction in 1996 in which “75 women of diverse backgrounds and ages” were transformed into a “computerized composite”.

Eventually transitioning into an active public face of the company, actress Adelaide Hawley Cumming began portraying the character of Betty Crocker in life from 1949; first appearing on television shows and in commercials, she later acquired her own show in 1951 and would play the character until 1964. Eventually, the fiction of Betty Crocker was revealed by Fortune magazine, who would label her a “fake” and a “fraud”; in spite of this, she continued to remain the public face of the company until it dissolved in 2007.

ADVERTISEMENT - CONTINUE READING BELOW

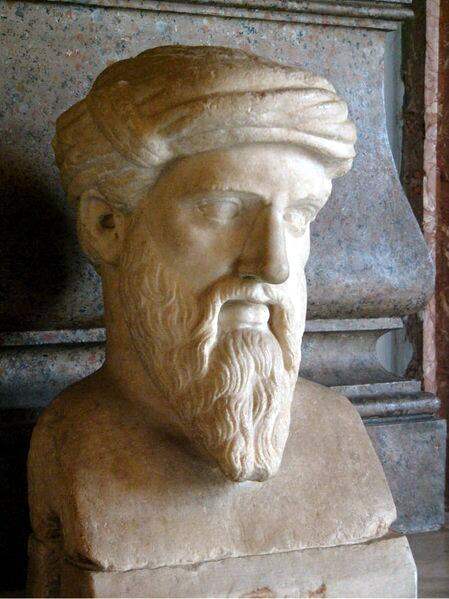

4. Pythagoras’ theorem, in spite of the name, was almost certainly discovered by multiple other people and not the Greek mathematician

Pythagoras of Samos (570-495 BCE) was an Ionian Greek philosopher and scientist, whose great works influenced several other ancient Greek legends including Aristotle and Plato and who is popularly accredited with the discovery of, among other mathematical findings, the eponymous “Pythagoras theorem”: a fundamental relation in geometry that states that the hypotenuse of a right-angled triangle is equal to the sum of the squares of the other two sides, most famously inscribed as a2 + b2 = c2.

Despite an estimable legacy of works attributed to him, no authentic writings of Pythagoras have survived to the modern day and extremely little is known about his personal history; in fact, the majority of the earliest sources on Pythagoras’s life are satirical, mocking the legendary figure as a charlatan and claiming that he “manufactured a wisdom for himself”. Much of the historical record is derived from later Greek and Roman biographies written several hundreds of years after Pythagoras’ death, offering either fanciful exaggerations or subtle understatements depicting him, in the words of Herodotus, as “not the most insignificant”.

Due to this uncertainty, it has been widely speculated whether Pythagoras was truly the genesis of the theorem that bears his name; in particular, whether the discovery was made in one location by one individual and proliferated thereafter or whether several separate discoveries were made independently of one another and the naming rights merely fell foul of Stigler’s law of eponymy. Historians have suggested that the theorem was well known to mathematicians of the First Babylonian Dynasty, existing over a thousand years prior to Pythagoras’ birth, with the Berlin Papyrus 6619 including a problem with the solution of the Pythagorean triple; similarly, the Mesopotamian tablet Plimpton 322, written between 1790 and 1750 BCE, retains a close similarity to this proof. Casting a wider net, the Baudhayana Sulba Sutra, dated to between the 8th and 5th centuries BCE of India, contains an algebraic statement of the eponymous theorem, and the classic Chinese text Zhoubi Suanjing provides a logical reasoning for the Pythagorean triangle, named the “Gougu theorem”, as early as 1000 BCE. Consequently, the current historical consensus is that “whether this formula is rightly attributed to Pythagoras personally, one can safely assume that it belongs to the very oldest period of Pythagorean mathematics”.

ADVERTISEMENT - CONTINUE READING BELOW

3. William Shakespeare might not have been the sole author of the works traditionally attributed to him, instead being the work of several others

William Shakespeare (April 1564 – April 23, 1616) was an English playwright, actor, and poet, who is broadly accredited with the authorship of 39 plays and 154 sonnets, in addition to several narrative poems and verses; many of these poetic and dramatic works, predominantly written between 1589 and 1613, are considered to be among the greatest examples of the English written language and remain at the heart of English culture.

Starting around 230 years after the death of Shakespeare, speculation begun concerning the authenticity of the supposed authorship of the works traditionally attributed to him; instead of the Warwickshire-born commoner, several alternative authors have been suggested including Francis Bacon, Christopher Marlowe, and most frequently Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford, in addition to theories of group collaborative authorship under a single name.

The arguments put forward by anti-Stratfordians follow a few key lines of inquiry, among which is that a commoner could not have displayed the necessary knowledge of the Elizabethan or Jacobean Court of the day; consequently, only an individual with access to such elevated social circles could have penned the legendary works. Furthermore, such arguments highlight the lack of documentary evidence for the life of William Shakespeare, with his surviving papers relating to matters of personal taxes and other banal subjects; this argument, it should be noted, overlooks the general lack of documentation for any commoners by any official offices during this time period. And finally, most prominent among the alleged evidence: that a commoner could not have received sufficient education and learning to become a master playwright, indicating a man of greater social position than the son of a glove-maker.

Whether true or not, the theory has been sufficiently convincing that numerous prominent public figures in recent years have expressed skepticism concerning the true authorship of Shakespeare’s works including Charlie Chapman, Mark Twain, and Walt Whitman; however, as it stands the current academic opinion rejects these opinions as conjecture and conspiracy theories.

Disclaimer: This author is compelled to state that they do not personally subscribe to the authorship theories concerning the works of William Shakespeare and fully believes that they are indeed the singular work of the Stratford-upon-Avon born commoner.

ADVERTISEMENT - CONTINUE READING BELOW

2. Jack the Ripper, the unidentified serial killer of Whitechapel, might have actually been multiple uncaught murderers

Jack the Ripper, also known as the Whitechapel Murderer or Leather Apron, was an unidentified serial killer responsible for the murders of at least five women in the Whitechapel district of London in 1888. The victims, all female prostitutes, were murdered through a deep throat cut, in addition to facial, abdominal, and genital-area mutilation, and the posthumous removal of internal organs; due to the latter activity, it was widely assumed that the killer possessed a detailed anatomical knowledge and possibly surgical training. It is presumed the murders stopped as a result of the killer’s death, incarceration, or emigration, but this is merely reasonable conjecture as the true identity remains undiscovered to this day.

The name “Jack the Ripper” stemmed from a letter written by an anonymous person claiming to be the murderer, known colloquially as the “From Hell” letter, and accompanied by a preserved human kidney supposedly taken from one of the victims; although it is widely believed today that the letter was a hoax by journalists in an attempt to heighten interest in the story, it created the longstanding impression that the attacks were the work of a single, particularly brutal serial killer.

In total more than 100 suspects have been suggested as potential “Rippers”, among which in modern “Ripperology” include barrister Montague John Druitt, barbers Seweryn Antonowicz Kłosowski and Aaron Kosminski, the latter of which were admitted to Colney Hatch Lunatic Asylum in 1891, and boot-maker John Pizer; contemporaneous speculation, interestingly, focused on an entirely different set of suspects ranging from Thomas Hayne Cutbush, a medical student institutionalized in 1891 after suffering syphilitic-induced delusions, and Frederick Bailey Deeming, who would emigrate to Australia in 1891 after murdering his entire family and later claimed in a prison-penned book prior to his hanging to be the Ripper.

One theory of particular note is the possibility that several killers were actively operating in the Whitechapel area of London, employing a similar modus operandi to mask their individual crimes. In addition to the five “canonical” Ripper murders, a further six were collectively part of the historic police docket as part of the “Whitechapel murders”, and prostitutes working the streets of London in the late-19th century were hardly safe even prior to the emergence of the alleged serial killer; with minor differences, but striking similarities, it is possible that the murders were the products of several intelligent psychopaths disguising their collective works under a popularly created and feared pseudonym.

ADVERTISEMENT - CONTINUE READING BELOW

1. Robin Hood was most probably not just one individual outlaw, but a pseudonym of many in an attempt to evade justice

Robin Hood is a legendary outlaw from English folklore, traditionally depicted as a skilled archer of noble birth who fights injustice in the Nottingham region of Britain during the reigns of King Richard I (r. 1189-1199) and King John (r. 1199-1216). Robbing from the rich and giving to the poor in an effort to defy the corrupt Sheriff of Nottingham, who according to some versions of the tale conspired with John to usurp the throne from the absentee king, accounts of Robin typically include several notable companions including his lover, Maid Marian, and his band of Merry Men; often depicted among these outlaws are Little John, William Scarlock (later Scarlett), and in more recent traditions Friar Tuck and Alan-a-Dale.

Although some historians claim that the character is a purely fictional aspect of the English folk canon, there is strong evidence that whilst an individual with the precise biography of Robin Hood might indeed have never existed that the name was used as a stock alias by outlaws during the 13th and 14th centuries. The earliest known references to such a person date from 1261, in the rolls of several English Justices as known nicknames of malefactors: persons who have committed a crime; eight such references exist between 1261-1300, offering strong credence to the theory that “Robin Hood” was an alter ego adopted by outlaws to maintain anonymity in the course of their crimes. Whether the inspiration for this alias was a real outlaw, possessing the story attributed to the legend, or whether the legend itself was fictional and merely appropriated by unassuming real-life criminals, is unknown, but it is highly likely that there were more than one Robin Hoods at various points across England.

Where do we find this stuff? Here are our sources:

“The Historicity and Historicisation of Arthur”, Caitlin Green, Arthuriana (2009)

“The Arthurian Legend before 1139”, Roger Sherman Loomis, University of Wales Press (1956)

“The Nature of Arthur”, O.J. Padel, Cambrian Medieval Celtic Studies (1994)

“101 Questions and answers on Confucianism, Daoism, and Shinto”, John Renard, Paulist Press (2002)

“Complete Works of Chuang Tzu”, Burton Watson, Columbia University Press (1968)

“Tokyo Rose: Orphan of the Pacific”, Masayo Duus, Kodansha International (1979)

“Tokyo Rose/An American Patriot: A Dual Biography”, Frederick Close, Scarecrow Press (2009)

“On the Reliability of the Old Testament”, Kenneth Kitchen, Eerdmans Publishing (2003)

“Moses”, Sholem Asch, Putnam Publishers (1958)

“The Secret of the Stratemeyer Syndicate”, Carol Billman, Ungar Publishers (1986)

“Edward Stratemeyer and the Stratemeyer Syndicate”, Deidre Johnson, Twayne Publishers (1993)

“Roots: The Most Important TV Show Ever?” BBC Culture.

“The Luddite Rebellion”, Brian Bailey, New York University Press (1998)

“The Art of War: Sun Zi’s Military Methods”, Victor Mair, Columbia University Press (2007)

https://www.history.com/topics/ancient-china/the-art-of-war

“John Henry: Tracking Down a Negro Legend”, Guy Johnson, University of North Carolina Press (1929)

“Who Was John Henry? Railroad Construction, Southern Folklore, and the Birth of Rock and Roll”, Scott Nelson, Studies in Working-Class History of the Americas (2005)

“Mary Magdalene: Beyond the Myth”, Esther De Boer, SCM Press (1997)

“Mary Magdalen: Myth and Metaphor”, Susan Haskins, Riverhead Trade (1993)

“Have we Homer’s Iliad?”, Adam Parry, Yale Classical Studies (1966)

“The Sagas of Ragnar Lodbrok”, Ben Waggoner, The Troth (2009)

“A History of Sparta, 950-192 B.C.” W.G. Forrest, Norton Publishing (1963)

“Adelaide Hawley Cumming, 93, Television’s First Betty Crocker”, The New York Times (April 28, 2016)

“Who Was Betty Crocker?”, Tori Avey, PBS Food (February 15, 2013)

“The Case for Oxford (and Reply)”, Tom Bethell, Atlantic Monthly (October 1991)

“William Shakespeare: A Study of Facts and Problems”, E. K. Chambers, Clarendon Press (1930)

“New Perspectives on the Authorship Question”, Richmond Crinkley, Shakespeare Quarterly (1985)

“Jack the Ripper: The Definitive History, Pearson Education (2003)

“The Man Who Would Be Jack: The Hunt for the Real Ripper”, David Bullock, Thistle Publishing (2012)

“The Origins of Robin Hood”, R.H. Hilton, Past and Present (November 1958)

“Robin Hood: Outlaw and Greenwood Myth”, Fran Doel and Geoff Doel, Tempus Publishing (2000)