The modern-day triumvirate comprising weapons of mass destruction is usually rendered as Nuclear, Biological and Chemical (NBC). Of these three in many ways, biological weapons may strike the greatest fear in the hearts of their potential victims. Both nuclear and chemical weapons are designed and their use geared towards the rapid demise of intended victims, although both do contain the potential for long-term effects which continue to kill for many years.

The use of nuclear weapons would, of course, be quickly known by survivors outside the killing range of the weapons, and events in Syria in recent years, and in Iraq years before, provide ample evidence of the use of chemical weapons against civilians and military targets.

Biological weapons contain hidden terrors because their use could cause epidemics of disease which may take time to fully unfold. Biological weapons can be deployed in the drinking water supply, the food supply, and in the air. Diseases which bring with them medieval horrors can be unleashed, without the dramatic explosions of bombs or rain of incoming missiles. Biological agents used as weapons can be deployed quietly, secretively, and even after their worst effects are felt may still escape scrutiny as the cause of death of millions.

While it is difficult to construct nuclear weapons and the means to deploy them while avoiding detection, many biological weapons can be designed under the guise of legitimate medical research. And there is precedent for their use, going back not just to relatively recent events, but to the days of antiquity. Here are several samples of the use of biological agents as weapons of war that have occurred in history.

ADVERTISEMENT - CONTINUE READING BELOW

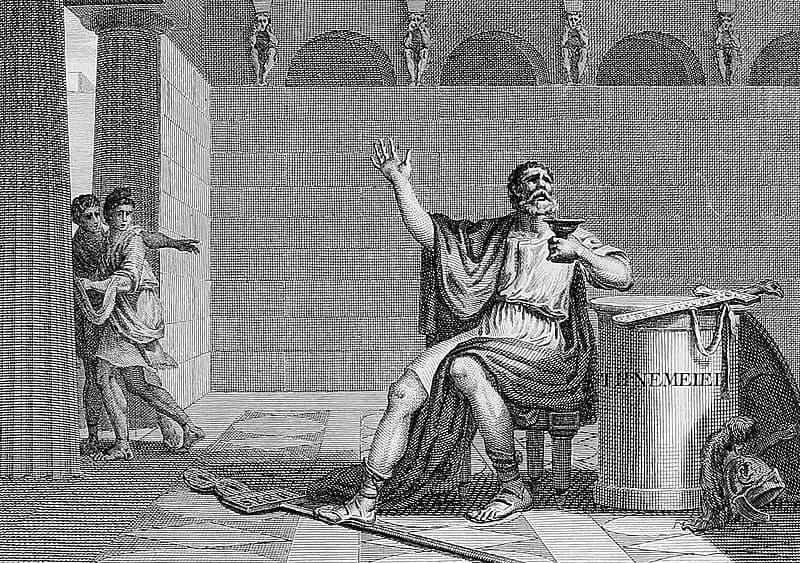

Hannibal of Carthage

Hannibal’s legend is centered on crossing the Alps and Pyrenees mountains during the opening phase of the Second Punic War, equipped with war elephants. Hannibal, despite ultimate defeat by the Romans, is known to history as one of the greatest battlefield tacticians of all time. In one of his lesser-known victories towards the end of his life, he directed a fleet in a naval battle, defeating the powerful Greek city-state Pergamon which was then allied with Rome.

Beset by enemies, Hannibal took shelter and service with Prusias I, ruler of Bithynia, a province in the region of Asia Minor. With Prusias providing refuge, Hannibal led a fleet of vessels into battle against those of Pergamon’s King Eumenes II. Knowing that his fleet was outnumbered by ships and men, Hannibal had his command gather venomous snakes and store them in clay pots aboard their ships, small enough so that each pot could be handled by one man.

He then sent a messenger to parley with his foe, in a manner deliberately calculated to be insulting and thus provoke a reckless attack on the perceptibly weaker fleet Hannibal commanded. When Eumenes attacked, Hannibal had his ships assume defensive positions alongside their enemies and the pots full of kraits, cobras, fer-de-lances, and death adders – some of the deadliest snakes known to mankind – were thrown into the hulls of the enemy vessels where shattering, they released their angry contents among the bare legs of the enemy.

Panicked by the attacks of the poisonous serpents, the Pergamonites were soon overwhelmed by their enemies, with many dying of multiple bites from the venomous weapons Hannibal had deployed. Hannibal’s use of biological weaponry in the form of poisonous snakes led to his last great victory. Throughout his military career, Hannibal was aware of the value of organic poisons. According to some historians, he died from self-inflicted poison, a bag of which he had carried on his person throughout his military career.