ADVERTISEMENT - CONTINUE READING BELOW

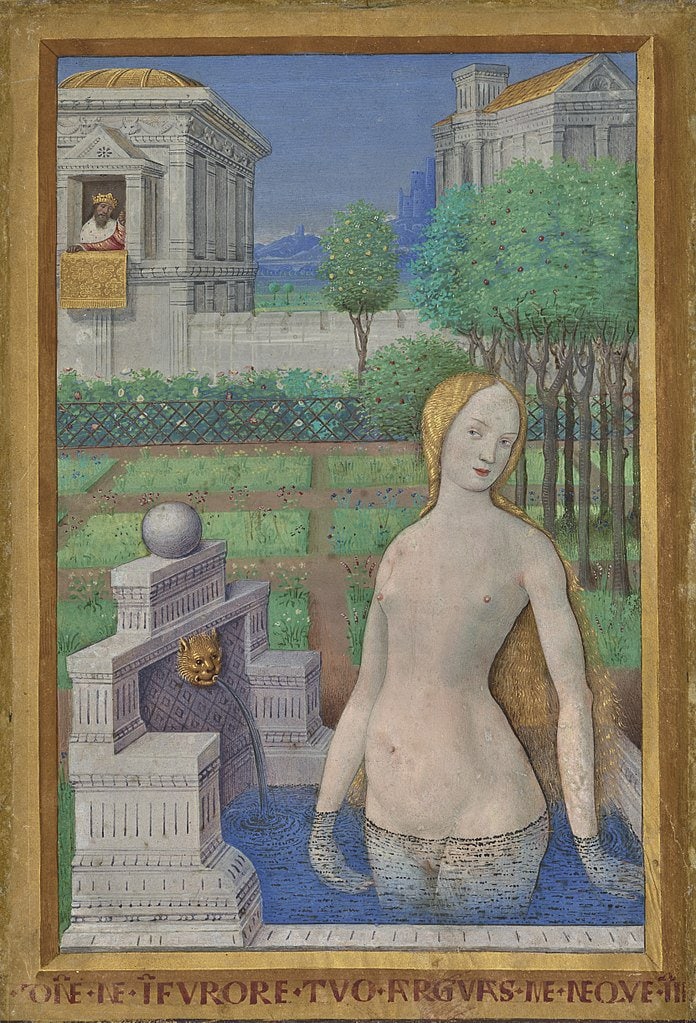

Bathing came to be seen as a self-indulgent luxury, hence sinful

In medieval Europe, from the Iberian Peninsula to the beginning of the Russian steppes, towns and larger communities typically emerged alongside rivers and streams. As communities grew, the freely running water became supplemented by wells and cisterns, the latter to capture rain water and store it for another day. Rain barrels in towns answered a similar purpose. But only in the homes of the wealthiest, and in the monasteries, which in the medieval period were often the same thing, was there anything resembling running fresh water. For anyone else, water had to be carried from the source to the home. Most homes, even the most humble, maintained a wash basin for the purpose of cleansing hands and face in the morning and before meals. Few used the precious liquid for anything else, except during special days set aside for the purpose of washing clothes and bodies.

ADVERTISEMENT - CONTINUE READING BELOW

Six days of the week were for labor. Taking time off for the wasteful luxury of soaking one’s lazy body in warm water was sinful. On the seventh day, the carrying of water, gathering of firewood, and act of heating and dispensing water for the purpose of lolling in it was a violation of the Sabbath. It was enough that clothes were washed on the day of the week assigned for the purpose. Since relatively few had more than one suit of outer clothes, it was usually only undergarments, called smallclothes, which were exposed to hot water and harsh soap. Bathing of the body was unheard of in winter, and often looked upon with considerable suspicion in the warmer months. The results were predictable. Bodies odoriferous from their own sweat, crawling with lice, fleas, and skin disorders, were the rule, from the most humble abode to the Royal palaces.