ADVERTISEMENT - CONTINUE READING BELOW

A Novel Argument Inspired by a Desire to Do Good, that Backfired and Led to Centuries of Horror and Misery

Las Casas’ argument introduced the then-revolutionary idea of slavery based on race, rather than the ancient and medieval slavery based on war and conquest. Before, ancient Greeks, Romans, and their medieval European successors had justified slavery based on the right of conquest. It was a race-neutral justification: those defeated in war and conquered could be enslaved. Caveats were sometimes carved out, such as the Spanish government’s prohibition of the enslavement of fellow Catholics. Conquered Muslims, Protestants, and pagans could be enslaved, regardless of their race, but not defeated Catholics. Nor could conquer non-Catholics who agreed to convert to Catholicism be enslaved. Las Casas gave the Spanish, and later the rest of Europe, a new and novel justification to enslave other human beings: their race. In this conception, Africans were marked out as fit for enslavement because they were Africans, period.

ADVERTISEMENT - CONTINUE READING BELOW

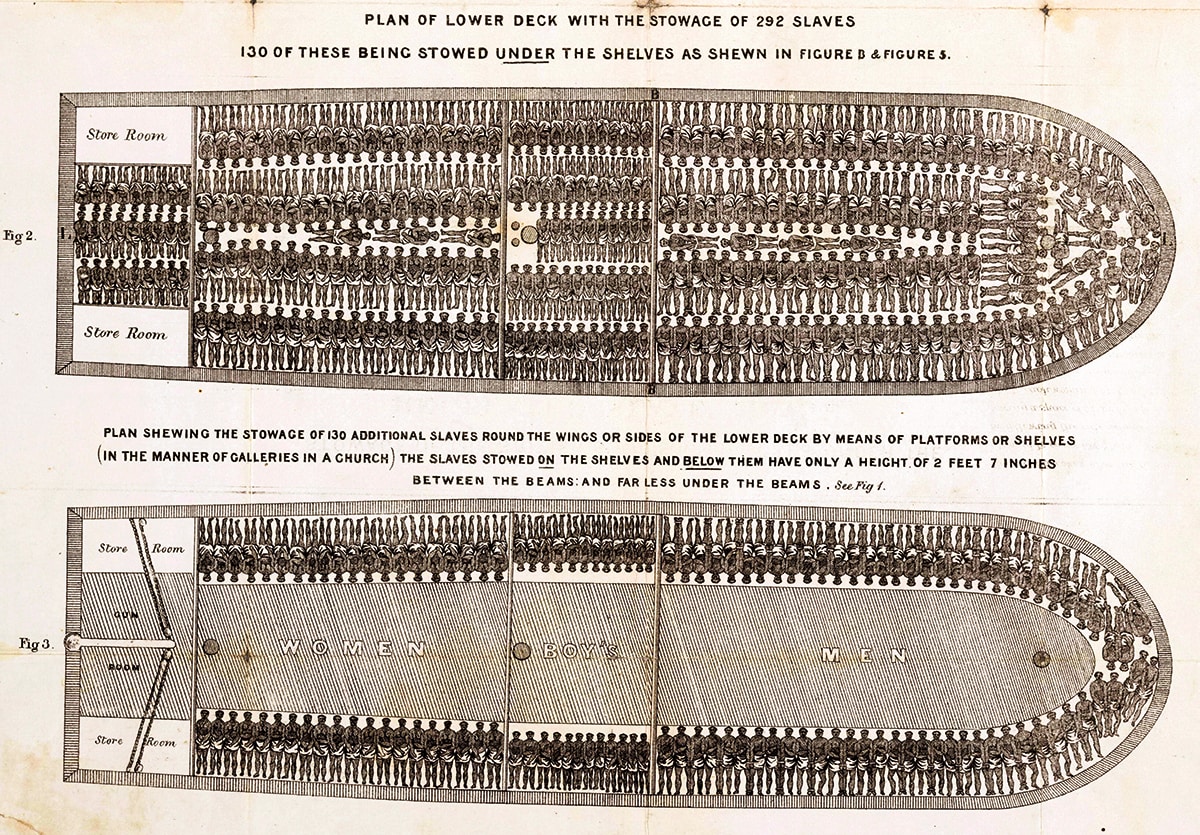

Las Casas eventually called for the abolition of all slavery. By then, however, the genie was out of the bottle. Europeans embraced his original idea of race as justification for slavery, and ignored his later retraction. The result was the transatlantic African slave trade, which lasted for almost four hundred years, from the sixteenth to nineteenth centuries. 12 to 15 million Africans were sent to the New World for a life of slavery that was often dark, cruel, brutal, and short. At least for those who survived the horrific Middle Passage from Africa to the Americas, in which millions perished. That was just the tip of the horror iceberg: for every single African who boarded a slave ship, up to five more perished in the violence that surrounded the capture of slaves and their transportation to the coasts and slave ships.