On retro television channels featuring the hit shows of the 1960s and 70s, the World War II sitcom Hogan’s Heroes, set in a German prisoner of war camp, retains its popularity. In the show, for anyone unfamiliar with its premise, the prisoners aren’t really prisoners at all but highly skilled and trained commandos tasked with operating behind enemy lines base of operations to help escaping prisoners get out of Nazi Germany. They also conducted sabotage missions as directed by their commanders in London.

Hogan’s Heroes originally ran from 1965 – 1971, building its audience in its early days in part from the popular prisoner of war escape movies The Great Escape and Von Ryan’s Express. In truth its depictions of the Germans as blundering nincompoops were inaccurate, and Allied prisoners of war did not conduct sabotage. They were too interested in getting home, and ingenious methods were developed to help them.

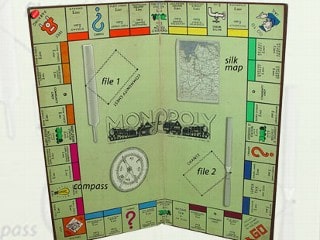

The Germans were efficient jailers, although they wrestled with the Allied prisoners’ proclivity for escaping throughout the war. Prisoners demonstrated great ingenuity (and courage) in both their methods of escape and their use of support systems, aided and abetted by offices and bureaus in London, Washington, and Geneva, and other sites. One of the means by which they were supported was via the provision of escape maps, tools, and money, and one of the means of providing these verboten items to the prisoners was through the innocent board game, Monopoly.

ADVERTISEMENT - CONTINUE READING BELOW

In 1935 the British printing firm of John Waddington Ltd, based in the industrial city of Leeds, acquired the rights to produce and market the game Monopoly in the United Kingdom and other sites throughout the British Empire. Waddington’s felt that the game’s Atlantic City New Jersey locations were too foreign to appeal to UK markets and replaced them with locations in and about London (the American Boardwalk is replaced by Mayfair, for example). This version became the standard throughout the British dominions with the exception of Canada, which retained the US locations and railroads. It was this British version that became well known in Europe.

In the early days of the Second World War, a series of military disasters befell the British, and large numbers of prisoners were soon in the hands of the Germans. Placed in camps throughout Germany, Poland, and for a time North Africa, these prisoners began to exhibit an annoying penchant – to their German captors – of escaping the bounds of their prisons. Few made it out of the Reich, but the Germans nonetheless had to devote ever increasing numbers of troops to guard their intractable charges. It was soon evident to the military high commands that escaping prisoners caused problems for the enemy, a situation which they immediately set about exploiting.