After the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, the United States mobilized as it never had before or since. Beating plowshares into swords, America began the Herculean process of shifting from a peacetime footing to one of total war. Industry was retooled from civilian pursuits such as manufacturing lipstick casings and converted to pumping out bullet cartridges; from producing typewriters to turning out tanks; and from assembly lines rolling out family sedans to rolling out heavy bombers by the thousand. More importantly, America mobilized her most precious asset: her manpower.

As late as 1939, the US had an Army of only 170,000 men, even as war raged in Asia and clouds of conflict gathered over Europe. By 1945, America had put 16 million men in uniform – a figure that, if prorated to current population, would be the equivalent of an American military numbering nearly 40 million.

ADVERTISEMENT - CONTINUE READING BELOW

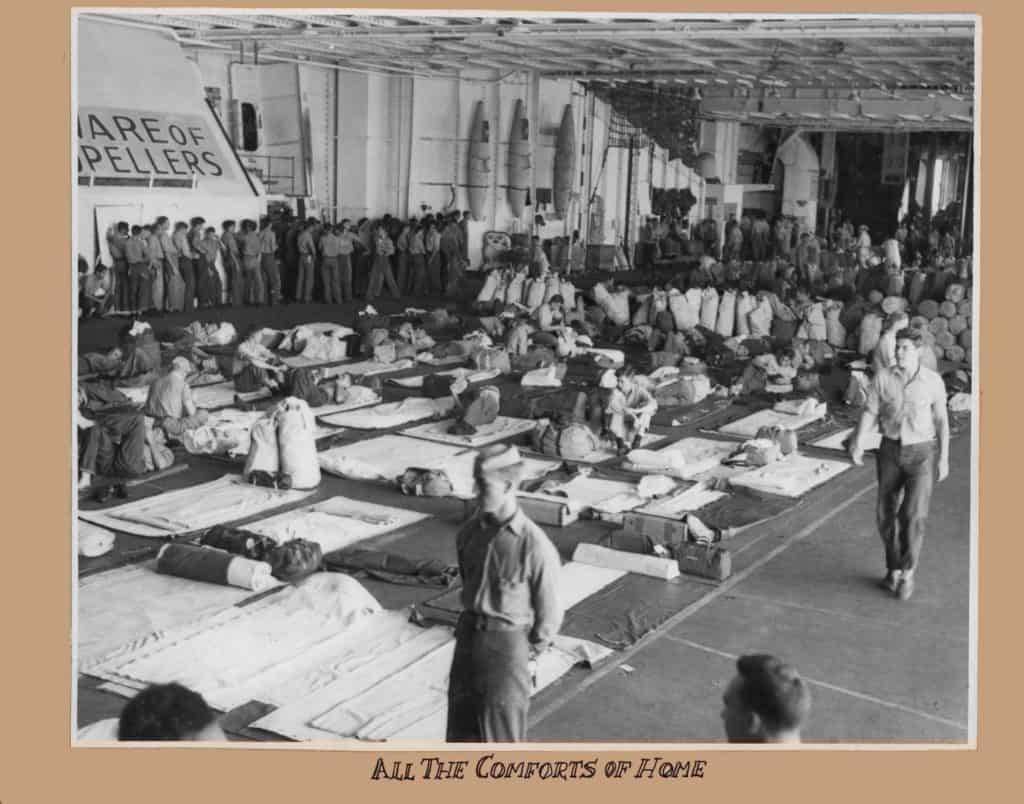

At war’s end, more than 8 million US servicemen, were stationed overseas, scattered all over the globe. The fighting was over, and it was time to bring our heroes home – heroes whose eagerness to return to civilian life was matched by the eagerness of their loved ones to see, touch, and embrace them once again. To that end, Operation Magic Carpet was conducted to repatriate America’s troops to US soil. The massive logistical effort was entrusted to the War Shipping Administration (WSA), an agency created during the emergency of WWII to coordinate, oversee, and operate America’s civilian shipping in support of the war effort.

Planning for Magic Carpet began in 1943. Even as transports crossed the Atlantic, laden with the troops who would help free a continent from the Nazi yoke, the WSA and the War Department drew plans for their eventual return. Priority was determined by the Advanced Service Rating Score – a pecking order based upon the principle that: “those who had fought longest and hardest should be returned home for discharge first”. Points were awarded for months of service, months of service overseas, combat awards, and dependent children. The more points scored, the greater the priority for shipping home and discharge.

In preparation, the WSA converted over 300 cargo ships into troop transports. Beginning in June of 1945, within a month of Germany’s surrender, the WSA began shipping American servicemen from Europe to the US. Following Japan’s surrender, the agency’s remit was extended to repatriate servicemen from the Pacific Theater as well.

Implementation of Magic Carpet began in earnest when the first ships set sail in June 1945, from the European Theater and crossed the Atlantic, laden with returning servicemen. The American buildup in Europe had averaged about 150,000 troops shipped across the Atlantic per month. After the war ended, Magic Carpet reversed the tide, returning US servicemen at an astonishing rate that averaged 435,000 men per month during a 14-month stretch, with a peak reached in December of 1945, when over 700,000 personnel were repatriated from the Pacific Theater alone.

ADVERTISEMENT - CONTINUE READING BELOW

To maintain the pace, the number of ships employed steadily grew from the initial 300 requisitioned by the WSA at the start of the operation. The motley fleet ranged in size from small vessels with a carrying capacity of only 300 troops, to behemoths such as the luxury liners Queen Elizabeth and Queen Mary, converted during the war into troop transports capable of carrying up to 15,000 servicemen.