Some might say Julius Caesar was the most influential figure in Roman history. Others might nominate Brutus, the man who drove out the last of Rome’s kings, or Augustus, who 700 years later essentially went on to became one. But although this figure’s admittedly less known, there’s another strong contender for being one of Roman history’s most influential: the humble pullarius, or “priest of the sacred chickens”.

The pullarius was responsible for keeping sacred chickens and using them to make divinations or “predictions.” These holy birds, which had been sourced from the island of Negreponte (now Euboea, near Athens), were kept unfed in their cages for a predetermined amount of time before being released and presented with some grain. If they ate the grain, the venture upon which the Romans were consulting them was deemed favorable. If they didn’t touch it, however, the venture lacked the god’s backing and was therefore to be abandoned.

This was just one of many forms of augury — not to be confused with “orgy”, though the Romans had plenty of those too — that completely consumed Roman decision-making. There were many ways of trying to divine the will of the gods through auguring. Observing and interpreting natural or manmade phenomena — a thunderstorm, perhaps, or an inauspicious chant by the crowd at the games — are a couple of examples. But the most common, ritualized, and legal methods of auguring were getting a priest to either read the entrails of a slaughtered animal or extrapolate meaning from the behavior of birds.

ADVERTISEMENT - CONTINUE READING BELOW

Augury was central to Roman policymaking; if the auguries weren’t good, the undertaking would be abandoned. If you think that’s insane, imagine how Rome’s enemies must have felt (frustrated, most likely; chickens being notoriously difficult to bribe). I mean it’s not like antiquity was lacking in genius. These were, after all, the centuries that produced Socrates and Plato; Cicero and Virgil. You might have thought one of Rome’s enemies would consider sneaking some food into the coops: satiating the sacred chickens’ hunger and thereby saving their city from marauding Roman forces.

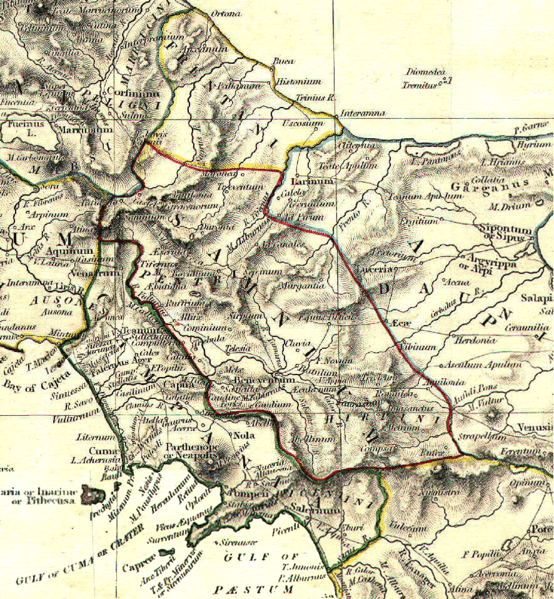

Then again, in the one episode for which we have any substantial information about the pullarius such guile wasn’t even necessary. For as important as the sacred chickens were to the superstitious practices of the Romans, on this one occasion they were simply ignored. The episode in question took place during the Third Samnite War (298 – 290 BC), fought between the Roman Republic and one of its southern, persistently troublesome neighbors, the Samnites.

The Samnites inhabited the area of what is now the Italian region of Campania — famous for cities such as Naples, and sites as Pompeii, Herculaneum, and of course Vesuvius. As native speakers of Oscan, the Samnites were linguistically and ethnically different from the Latin speaking Romans. They were politically autonomous too, eventually bringing them into conflict with territorially snowballing Romans.

ADVERTISEMENT - CONTINUE READING BELOW

This wasn’t the first time the two powers had come to blows. As the name of the war suggests, they had already fought two wars, in the late fourth century BC, when Rome began expanding southwards. Rome had won both, but not without suffering some serious and humiliating defeats, particularly at the Caudine Forks in 321 BC. The Third Samnite War wouldn’t be the last conflict between the two either. The Samnites were the last to hold out against the Romans during the so-called Social War of the 90s and 80s BC; an effort that ushered in their ethnic cleansing under the ruthless Roman general Lucius Cornelius Sulla.