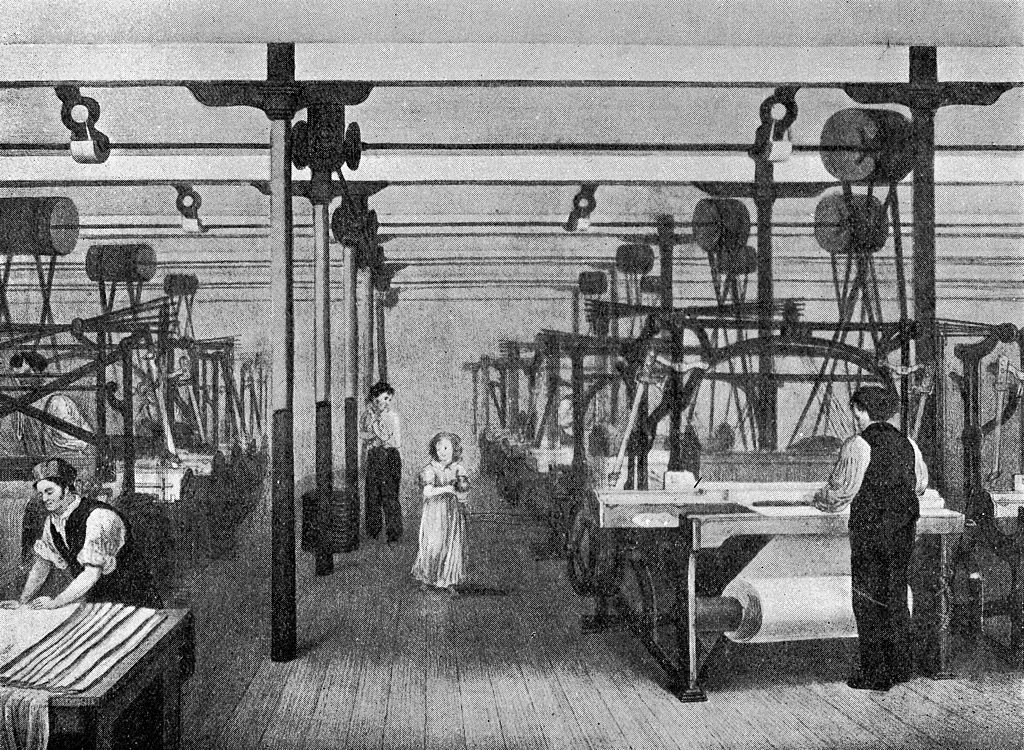

Five-year-old children today toil over learning math and tying their shoes. They sweat after a day of running around a playground during spirited games of tag. But just over one hundred years ago, a five-year-old might toil in a textile mill and sweat after a day of picking cotton. In the 1800s and early 1900s, children could work. And work they did, some up to fourteen hours a day. Child labor in the United States is as old as the colonization itself, but in the industrial era, reformers noticed, and loudly demonized, the practice. When they hired photographer Lewis Hine, however, the movement caught the attention; seeing the practice of child labor is a lot different than merely hearing about it. Hine’s work changed the nation’s understanding of child labor in the early 1900s. While Hine’s own story is well known, there are shocking stories behind each of his images.

ADVERTISEMENT - CONTINUE READING BELOW

Child Labor is as Old as Labor Itself

Children have always been part of the labor force. They worked on family farms, sold food and goods from carts at markets, and have even been horrifically enslaved. As industrial technology advanced, children sought jobs in factories and mines, working heavy machinery, using their small stature to access places adults couldn’t reach. From 1890 to 1910, roughly eighteen percent of children between ten and fifteen years old were employed. They had to work, even if the job was dangerous, and even if it meant they couldn’t go to school. Low-income children were expected to take jobs and give their wages over to their families. It was a means to support their basic needs, even if their education and development suffered. But as the United States became a highly industrialized nation and slavery abolished, inexpensive labor was necessary for long-term success in many industries.