ADVERTISEMENT - CONTINUE READING BELOW

The Unlikely Great Civil War Cavalry Commander Who Hated Horses

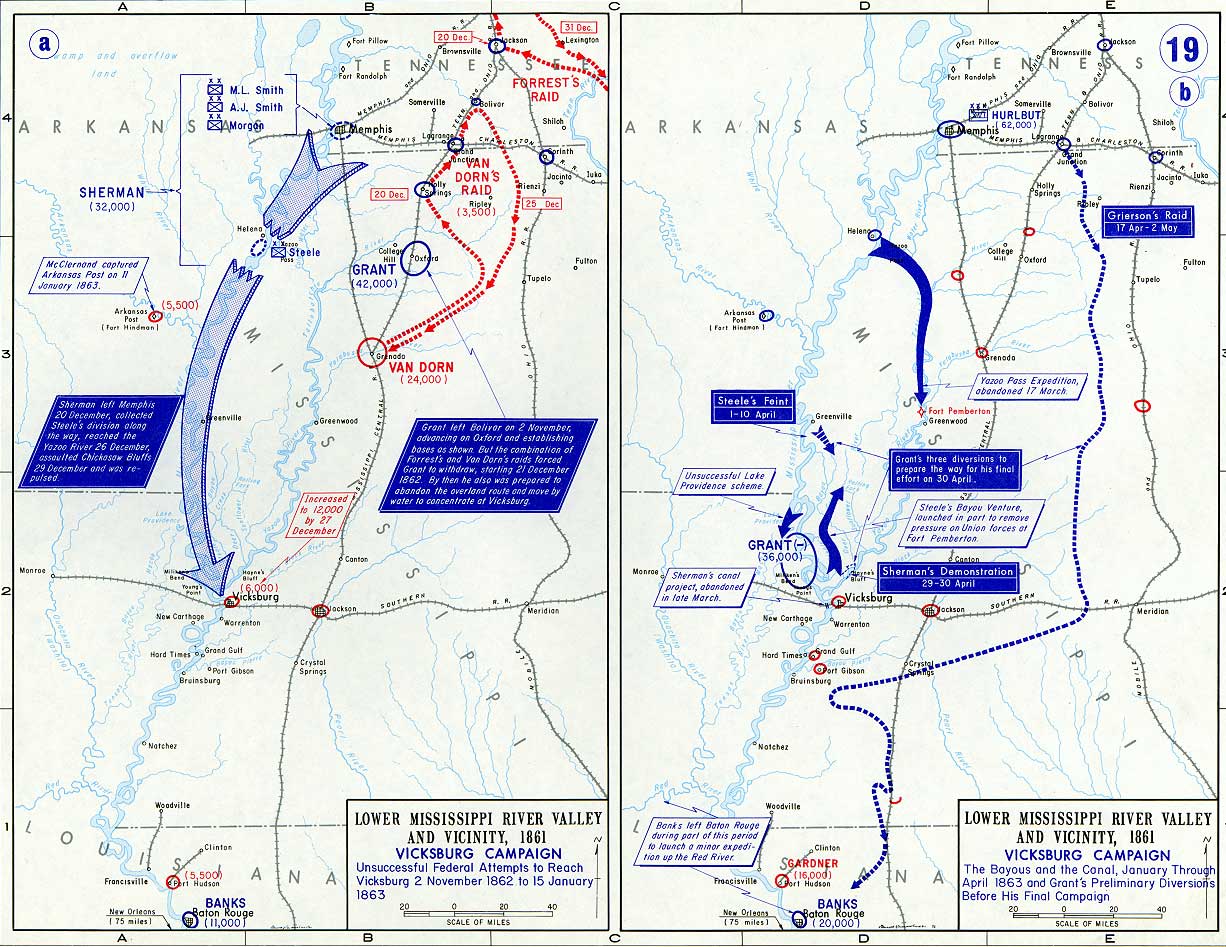

Benjamin Grierson was one of the Civil War’s most effective cavalry commanders. Few could have predicted that he would have such success commanding horsemen, seeing as how he hated horses. On April 17th, 1863, Union Colonel Benjamin Grierson led a cavalry brigade of 1700 horsemen out of La Grange, Tennessee. He took them southward to plunge deep into Mississippi, in a raid that would traverse the length of that state, and reemerge at the other side and the safety of Union lines in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. En route, the raiders discomfited the enemy and disrupted his communications. They tore up railroad tracks, destroyed bridges, wrecked Confederate installations and facilities, and otherwise wrought havoc and sowed confusion throughout Mississippi.

The raid sought to inflict significant damage, both physical and to the enemy’s morale. It was also intended to be the opening salvo of the Vicksburg Campaign, and act as a diversion from General Ulysses S. Grant’s planned attack against Vicksburg, Mississippi. Until then, Confederate cavalry had been markedly superior to that of the Union, literally riding circles around them. Thus, an additional motive was to demonstrate what federal horsemen could do with a daring exploit of their own to match the headline-grabbing ones of Confederate cavalrymen like J.E.B. Stuart and Nathan Bedford Forrest.

A Civil War Raid That Shook the South

A former music teacher who hated horses, Colonel Grierson led his cavalrymen as they travelled light. They packed only five days’ worth of rations for what planners envisioned would be a ten-day mission, forty rounds of ammunition, and oats for their mounts. Preceded by scouts in enemy uniform, they rode for 600 miles through Confederate territory that had never before seen enemy soldiers or felt the touch of war. Mississippi felt it now, and panicked as Union horsemen burned storehouses, tore up railroads and twisted them atop burning crossties, freed slaves, wrecked bridges, destroyed trains, and put commissaries to the torch. Throughout, Grierson peeled off detachments and sent them on feints to baffle and confuse the enemy about his actual whereabouts, intentions, and direction of march. The raid was a smashing success, literally as well as figuratively.

ADVERTISEMENT - CONTINUE READING BELOW

Grierson’s cavalrymen greatly damaged Southern property and morale. Although vigorously pursued by Confederates, the Union cavalry eluded their pursuers while causing mayhem in the enemy’s heartland. In a fifteen-day-rampage behind enemy lines, Grierson’s men lost only three killed, seven wounded, and nine missing, before they crossed into the safety of Union lines near Baton Rouge, Louisiana. In addition to its immediate impact, the raid demonstrated Union soldiers’ ability to live off the land within Confederate territory. That started the gears turning in the mind of General William Tecumseh Sherman about the vulnerability of the Confederacy’s interior, which he compared to soft innards surrounded by a brittle shell. A year and a half later, Sherman led to the destructive March Through Georgia, then the even more devastating March Through the Carolinas that sealed the Confederacy’s doom.