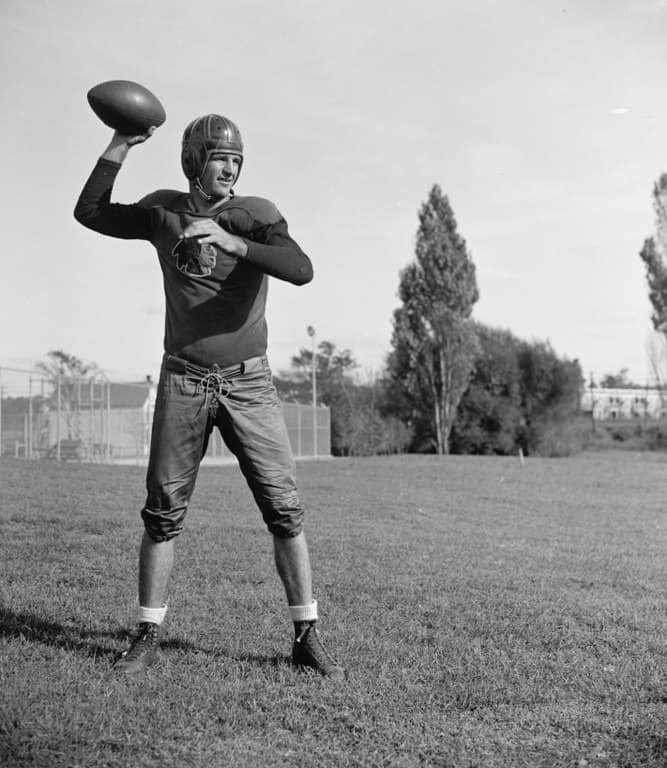

December 7, 1941, was a day of sunshine in Washington, D.C., capital of a nation neutral in a world at war. President Roosevelt relaxed with his stamp collection at the White House that afternoon. About 27,000 football fans jammed into Griffith Stadium to watch the Washington Redskins and Slingin’ Sammy Baugh play the Philadelphia Eagles. A Redskins victory, though an upset, would place the Washington squad in the NFL playoffs.

The kickoff was set for 2 PM. As the game unrolled, fans began to notice a stream of public announcements for noted reporters to call their offices and columnists to contact their editors. They were followed shortly by calls for senior military personnel to report to their commands. Calls for FBI officials to report for duty followed. Washington’s team management learned from the newswires of the attack then underway in Hawaii and elected not to announce it to the crowd.

ADVERTISEMENT - CONTINUE READING BELOW

The calls for personnel to report for duty persisted throughout the game, and by the end (the Redskins prevailed, 20-14) rumors of war in the Pacific were rife among the crowd. Cab drivers, listening to radio reporters, shouted the news to passers-by. Some claimed a decisive crushing of the Japanese attackers, others the American fleet had sortied to counterattack. Others were far closer to the truth, by then known to FDR in the White House, his beloved stamp collection forgotten for the moment. A decision to keep the true extent of the disaster at Pearl Harbor from the American people was made immediately. That decision, and subsequent events, led to eight decades and counting of speculation, rumors, and conspiracy theories over what happened before and during the attack on Pearl Harbor. Here are some of the myths and conspiracy theories about Pearl Harbor and America’s entry into World War II.

ADVERTISEMENT - CONTINUE READING BELOW

Americans weren’t expecting war with Japan in late 1941

Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, the United States Navy planned for an eventual war with the Empire of Japan. The Navy’s War Plans Department prepared and continually modified Plan Orange, with Orange representing Japan. An additional hypothetical plan, Plan Red, addressed the possibility of the United States at war with Japan and Great Britain simultaneously. The combined plans supported the argument for a two-ocean Navy, with powerful battlefleets in both the Pacific and Atlantic. The rise of Nazism and German nationalism negated much of Plan Red (though the plan was updated into 1939). Japanese militarism, and expansion in Asia, added urgency to Plan Orange. By the late 1930s, the US Navy was under a program of massive modernization and expansion, including new battleships, aircraft carriers, heavy cruisers, and support ships. Meanwhile, Japanese aggression in the Pacific continued unabated and even increased.

The United States used diplomatic moves, as well as economic sanctions, to protest Japan’s invasions of China and Manchuria. By the 1930s, nearly all of Japan’s oil was imported from the United States. The US also provided Japan with coal, iron ore, and scrap metal. Gradually, FDR imposed restrictions on all, but the Japanese continued to purchase most of their oil from the United States. In 1940, the Germans conquered France. Japan cast a covetous eye on the French colonies of Southeast Asia and their rich rubber plantations. Japanese troops occupied French Indochina, forcing Roosevelt to suspend aviation fuel imports from the United States. Japanese assets in the United States were frozen. Japan was thus forced to either suspend its expansion and withdraw from its conquests or go to war to expand them into the oil fields of the East Indies. They chose the latter.