ADVERTISEMENT - CONTINUE READING BELOW

2. The death rate on voyages was appalling

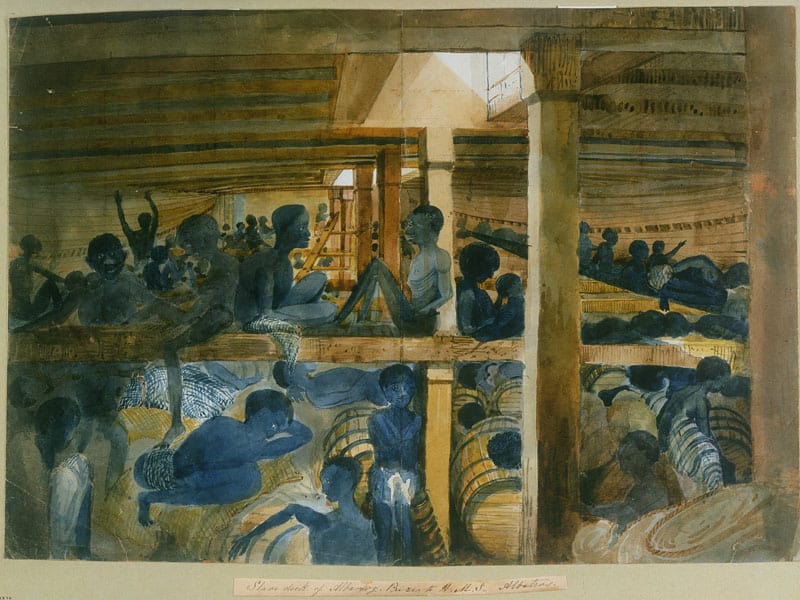

A voyage from equatorial West Africa to South or Central America took 10-12 weeks in the 16th century. As ships improved in size and speed, the time spent at sea was reduced, but it still presented a lengthy crossing. To the traders, slaves were cargo. A perishable cargo. Each person lost during the long voyage meant a reduced profit for the traders. Therefore, it was in the best interests of every trader to ensure his entire cargo arrived safely at its destination. Yet the Africans suffered miserably during the passage. They were carried in the same manner as livestock, and so regarded by the Captain and crew. No sanitation facilities existed for their use. Packed in as tightly as possible, disease grew rampant on the ships. Slave ships could be smelled almost as soon as they came into sight if they were upwind.

Deaths among the Africans reached upwards of 25% on some voyages. On average over the centuries of the trade, they were 15%, probably over 1 million people according to some estimates. In the 16th century, they were the highest per voyage, due to the length of the voyage and the harsh conditions. Scurvy, dehydration, dysentery, diarrhea, and suicides all added to the death rate. Many Africans, weakened by the voyage, died shortly after reaching their destination. The death rate among sailors manning the ships also was high, with sailors dying from the effects of harsh punishments, and diseases contracted from either the Africans aboard or while in equatorial Africa. Most common sailors hated the slave ships. Some Captains provided better food for the Africans than their crew, reasoning the more which survived meant higher profits. Conversely, crewmen who died did not need to be paid at voyage’s end.