American trust in the news media coincided with a brief period of time during which most Americans trusted their government as well. There’s little wonder it was short-lived. Since the earliest days of the republic, Americans have expressed distrust of the media, which in the early days was limited to newspapers and magazines. Then, as now, those relied on advertising revenues, rather than subscription fees, for their income.

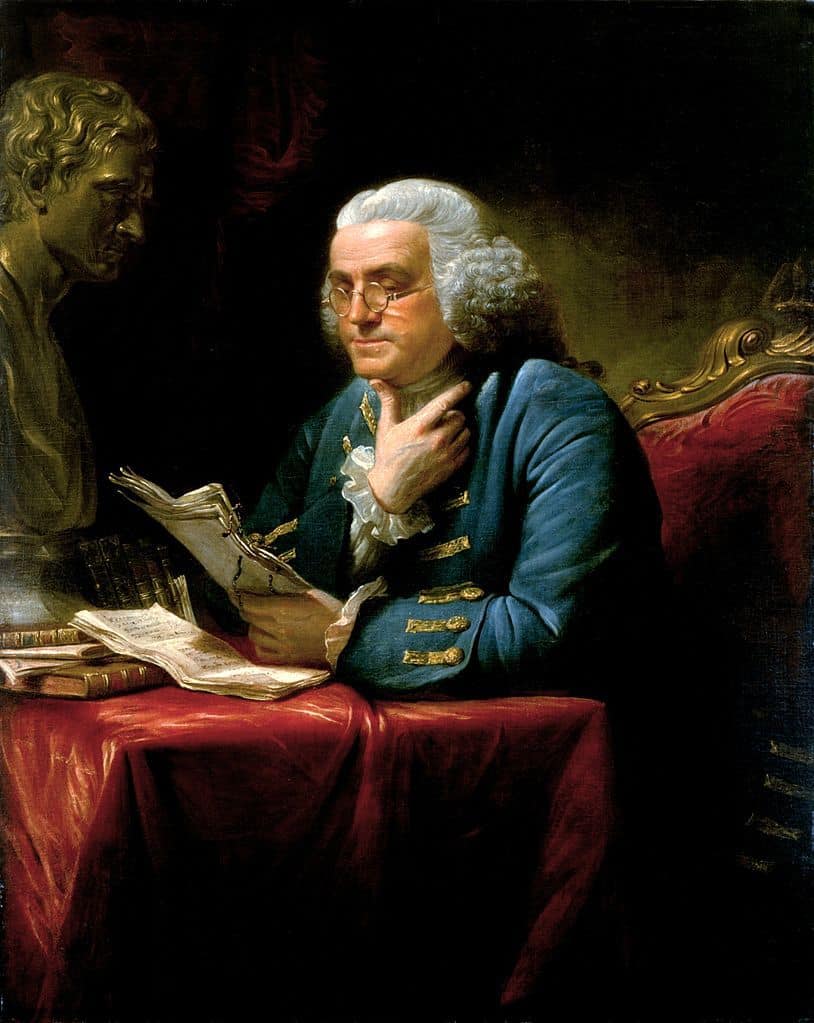

The earliest newspapers were usually produced by printers, a sideline which generated publicity for their services, as well as expressed their opinions regarding the events of the day. Benjamin Franklin was among the most successful. He lobbied for the 1792 Postal Act, in which the fledgling US government in effect subsidized newspapers by mandating delivery fees to be charged. At that time a vigorous press was deemed essential to democratic government.

A first-class letter delivered by the Post Office cost anywhere from six cents to 25 cents, depending on the distance it traveled. A newspaper traveled the same distance for less than two cents. The recipient paid the postal charges. In colonial America, newspapers thrived by publishing attacks on the governments of the colonies, and suppression of the press became commonplace prior to the Revolution.

As a result, the Founders ensured the protection of the free press in the Bill of Rights, in the new state constitutions, and in local laws. Succeeding politicians soon learned to regret their position. “Nothing can now be believed which is seen in a newspaper”, Thomas Jefferson wrote in exasperation in 1807. Yet much of the public did believe them. Here is the story of when Americans trusted the media, and how that trust eroded over time.

1. Prior to the Constitution, pamphlets served as the chief source of political discourse

Before and during the American Revolution, printers and political leaders seldom used the newspapers to express their views on politics. One reason is that both the Royal governments in the colonies, and the rapidly growing patriotic movement, took action against newspapers which expressed views contrary to their own. Newspapers focused on the news received from other papers, rather than local affairs. Shipping and mercantile news dominated the papers of the eastern cities. Reports of local crimes, social affairs, and other community news were relegated to the back page, if covered at all. Advertising and business news dominated the newspapers, including shipping news, auctions, the arrival of special goods from overseas, and so on. Political discourse was present but to a lesser amount. Political views were instead presented in pamphlets, prepared and distributed to shape public opinion.

One of the most famous such pamphlets, Thomas Paine’s Common Sense, argued the logic of independence for the United States before it had become a major subject of debate in the Continental Congress. Another, The Crisis, rallied the public during the disastrous (for the Patriots) year of 1776. Following the Revolution, pamphlets led to the cry for a more effective form of national government. Yet the three American founders who shaped the arguments supportive of ratification of the new Constitution chose to present their vision in newspapers. The Federalist Papers, as they came to be called, appeared in American newspapers in 1787, written under the pseudonym Publius, by Alexander Hamilton, John Jay, and James Madison. The debate over the Constitution shifted American newspapers to standing as primarily partisan political outlets. They remained as such for much of the first eighty years of United States history.